A brief history of American museum catalogs to 1860

Cataloging History, Part 1

(“Cataloging History” is a four-part series on the history and theory of museum and exhibition catalogs, focusing on the 1853 New York Crystal Palace. This first part considers the early history of this genre, tracking its roots to the catalog of the Museum Wormianum and the Louvre, and exploring the variety of uses to which early American museums put published descriptions of their collections and exhibitions. Part 2 looks in detail at the catalogs and guides published by and about the 1853 New York Crystal Palace. Part 3 considers the catalog as physical and digital object examining the affordances of each of these forms, what it encouraged and allowed. Part 4 applies the tools of the digital humanities to explore the Crystal Palace catalogs as digital object. What can we do when we turn the catalog into a database?)

Introduction

How do you describe an exhibition? Museums and exhibitions are multi-media, multi-sensory places. Full of objects, of course, each of them complicated, three-dimensional things with no end of details that can never be fully described. The objects are displayed in ways that have particular meanings, whether hung on walls or under glass in a cabinet or arrayed behind a velvet rope. They are arranged so as to create juxtapositions that make a point, or tell a story.

There’s an audience, too. Visitors, interacting with the objects — looking, touching, talking. Interacting with each other. In some exhibits, there are people guarding objects, explaining them, sometimes selling them. A visitor walking through an exhibit constantly makes choices: Where to look? What to touch? Which way to turn? What questions to ask? Exhibits are humming, buzzing, multimedia places, alive with sound and energy.

The descriptions of exhibits: not so much. Museum catalogs have a variety of purposes. They serve as a tease for those who might visit. For visitors, catalogs are guidebooks and vade mecums. What’s important? What does it mean? They’re useful after the exhibit too, to carry home memories. For those who can’t make it to the exhibition, the catalog serves as a stand-in, reproducing in some small way — as list, as description, sometimes as floorplan — what has been missed.

Catalogs also serve as a record of what was there. For art museums, catalogs are key pieces of evidence for provenance. For historians, they offer a view into a moment of carefully considered choices, a curated selection of things that seemed worth saving, or showing off.

Consider, then, the history of the catalog.

Some Early History

Samuel Quiccheberg’s Inscriptiones of 1565 may be the first treatise on museums, but it is neither a catalog not a treatise on museum catalogs. Quiccheberg mentions catalogs of books and coins, and suggests the importance of catalogs for collectors, but says nothing about public catalogs.

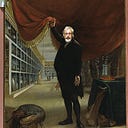

The famous image of Ole Worm’s museum (above) is from a catalog of his collection, published in 1654. (That’s one thing that makes the Musei Wormiani a precursor of the modern museum.) Worm’s catalog is, as its title states, a “history of rare things.” It uses the collection to discuss topics in natural history.

The modern museum catalog — a checklist — comes into existence with the public museum. The Louvre’s first catalogue in 1793, includes, writes Fritz Keers, “the essential features”: a printed list of objects in the collection, in systematic order — in this case, the same order as their hanging — and including descriptions which facilitate identification of the objects by the public.” This was a catalog a visitor might carry into the exhibition.

Early American Museum Catalogs

The first published American museum catalog was for Peale’s museum. Peale and co-author A.M.F.J. Beauvoir outlined the purpose of their 1796 “scientific and descriptive” catalog of his Philadelphia museum. He wanted the catalog to be “as useful as possible,” to “excite a taste for the science of natural history.” It was intended to be “useful, not only to those who occasionally visit the Museum; but also to those who, already, having some general acquaintance with Natural History, may wish to give the subject a more particular attention.” Peale’s catalog was a teaching tool; it was as much a textbook as a guide to the exhibits.

The 1821 Catalogue of the Articles in the Museum of the East-India Marine Society, in Salem is very different. It lists most of the collections of the museum in the order in which they arrived. Shells were listed by genus and species, coins in chronological order — except for coins from exotic places like China, which seemed outside of history. This was more an inventory, a checklist, than a guide to visiting the museum. Its purpose seems to be to brag about the extent of the collections, and to acknowledge donors.

The 1825 catalog of the New York Anatomical Museum offers a good example of the third type of museum catalog, the guide to an exhibition. It was explicit about its purpose: “Public utility, and the advancement of science, are the great objects of all cabinets; every method, therefore, which may promote these ends, should be adopted.” That meant good organization and explanation, and a publication aimed at students, “that they may see what the collection contains, and know what they see.” Students would carry the catalog into the museum.

Over the next few decades, while the publication of trade catalogs took off, only a few museums published catalogs. I’ve found only about twenty published museum catalogs in the US before 1865. By the 1850s, there seems to have been a feeling that catalogs are important, but hard to do.

The first catalog designed to describe the exhibit, not the objects, that I’ve found is this one, from Boston’s 1845 Chinese Museum. (This is the fourth type of catalog.) The museum was designed to give visitors a feel for China — to make a greater “impression on the mind” than books could. The cover explains the importance of things on display: “Words may deceive, but the eye cannot play the rogue.” The exhibit, the introduction to the catalog states, “with the aid of the descriptive catalog or guide, will give the visitor a better knowledge of this curious people than can be acquired by reading the most faithful descriptions alone, or even by a transient visit to China.”

This catalog served several purposes. It directed visitors through the museum, by means of numbered displays. The catalog describes the dioramas in great detail, offering cultural and historical context, and builds on these descriptions to tell a broader story. The diorama of Chinese mandarins, for example, describes the meaning of their clothes, and then proceeds to discuss their training, and education in China more generally. It offered translations of Chinese writing, and offered explanations of things that visitors might find off-putting, or peculiar. It included Chinese voices, both Chinese people as tour guides and quotes taken from travel writers, as well as extensive excerpts from books about China and histories of China. The 200-page catalog uses a description of the museum exhibitions to serve as an introduction to China and Chinese history.

Some natural history museums published catalogs starting in the 1840s. Mineral and shell collections lent themselves well to catalogs. The catalogs of other natural history collections were less descriptions of the collections than descriptions of flora and fauna based in part on museum collections — that’s what Spencer Baird did with his Smithsonian publications on the birds and mammals of North America.

In 1846, the Regents of the State University of New York were asked to determine what to do about the state’s cabinets of natural history that they had recently been given charge of. They needed more funding, of course, but also a catalog. “It appears indispensable to its safe-keeping, as well as to its utility, that there should be a full, descriptive catalogue of the articles contained” in it, they wrote. They were imagining a catalog as an annotated list. “None such exists at the present time,” and none had ever been prepared. In the meantime, the curator put a copy of the Natural History of the State of New-York in the museum, “for the purpose of examination and comparison.”

New York City Exhibitions and their Catalogs

Before 1850, there were few museums or art galleries in New York City. There were annual fairs, like the Fair of the American Institute, to show off machines and manufactured goods. Carrie Rebora Barratt, in her essay on antebellum New York City art exhibitions, describes the city in this period as a place with few experts, impromptu exhibitions, and dubious auctions. Two major art institutions, the American Academy of the Fine Arts and National Academy of Design competed with “displays in store windows, hospitals, artists’ studios, patrons’ parlors and other disparate spots.”

The National Academy was showing the best of American paintings. It published guides to its exhibitions. These were intended to be carried into the exhibit; paintings were identified by number. It goes further than simple description to tell you what to think about a painting — in this case, by a related poem.

The Dusseldorf Gallery opened in 1849. Its catalog seems aimed at an audience that’s not sure of its ability to make judgements about art. It begins with ten pages of “Extracts from the Press of New York,” describing the exhibition. The titles and artists are listed for each painting, and for many of them, there’s an excerpt from a newspaper review of the exhibition. Comphausen’s “A Castle Invaded by Puritans in the time of Charles I,” we are told, is “admirable as a composition, and full of life-like and startling contrasts…There is history and character in every personage.” Some paintings have several pages of commentary and criticism quoted from newspapers, books, and magazines. These early art exhibit catalogs focused on explaining what a visitor saw — or more precisely, explaining how the visitor should look at and understand what he or she saw.

By the 1850s, things had changed. Historian David Jaffee notes that 1850s New York was a visual experience, “a spectacle.” One key element — one of the things that made it modern — was the prominence of places where things were put on display. Jaffee notes that these visual experiences were made available to people across the country. New York firms like Harpers and Currier and Ives pumped out images and descriptions that shaped the ways that Americans imagined not just New York, but the very idea of a city.

The most modern stores offered arrays of objects for visitors to examine and purchase. Some these were cutting-edge visual enterprises like Appleton’s books and stereograph stores. Others were the new “Broadway palaces,” the retail stores that to my eye look a lot like museums. Many of these stores published catalogs of their goods.

Walt Whitman captured the spirit of these in his 1856 “Broadway, the Magnificent!” — which includes “Leaves of Grass”-style lists of what’s on display in each store:

Broadway! … the priceless wealth lavished every where with unsparing hand, heedlessly poured in its huge windows, or seen through its wide-open doors — the pictures, jewelry, silks, furs, costly books, sculptures, bijouterie, plate, china, cut-glass, fine cloths, fabrics of linen, curious importations from far-off Indian seas, grotesque wooden figures made in Japan, bronze groups painfully true to life, a deer struck by the hunter, a dying bird, the Madonna, the Crucifixion, superb engravings, photographs, landscapes, historic groups, each bearing a part in the most stately exhibition of magnificent Broadway.

Henry James, looking back on the 1850s, remembered the excitement of the art market on Broadway:

“Ineffable, unsurpassable those hours of initiation which the Broadway of the ‘fifties had been, when all was said, so adequate to supply. If one wanted pictures there were pictures….”

There were other public exhibitions and museums, too, but not many. The New York Times wrote in 1852:

There is nothing that strikes the foreigner with greater surprise than the total absence of anything like public institutions in the City of New York. [In European cities] there will be a museum, a picture gallery, a library, a botanical garden, a zoological collection, or something of that kind, free to all comers, and particularly interesting to all tourists.” [New York], the next great city of the world, has only Barnum.

That’s not quite true. The efflorescence of visual display meant that museum-like displays were popular; it’s just that most weren’t free and public and educational. There were medical museums, a phrenological museum.

In Brooklyn, there was the Naval Lyceum museum. The United States Naval Lyceum had been founded in 1833 at the Brooklyn Naval Yard. Building on the ideals of the naval reform movement and the lyceum movement, as well as contemporary ideas about science, history, material culture, and display, the naval officers who curated it gathered significant collections of historical relics, natural history and ethnographic artifacts, as well as a large library. The New York Times memorably described the place in 1852 as an “olla podrida [a Spanish stew] of queer things pining away its sweetness in the desert air of the Brooklyn Naval Yard.”

Storefronts, museums, galleries, expositions; all of these were highlights of the city, both for residents and visitors. They were, in many ways, new inventions of the era; they were novel, and needed explaining. Catalogs helped to do that.

In 1855 and 1856 the Naval Lyceum published a catalog of its collections, the “Iconographic Catalogue of the U.S. Lyceum, at the Navy-Yard, Brooklyn, NY.” Written by the Lyceum’s librarian — probably J. W. A. Nicholson, a naval officer just back from Perry’s Japan expedition — it is a remarkable publication, a meditation on the artifacts of art, science, and history. It provides us with the museum’s view of the collection: a sense of the categories it used, the rationale of collection and display, the meaning they saw in them.

The “Iconographic Catalogue” was designed not for visitors, but rather for those who could not visit the museum. It was published in installments in the foremost naval publication of the day, The U.S. Nautical Magazine and Naval Journal, where it hoped to reach “that class of readers to whom it is most desirable.” It uses the artifacts in the museum as the opportunity to teach on a vast range of topics. The model was likely the recently published Iconographic Encyclopaedia of Science, Literature, and art. systematically arranged by J.G. Heck. This was museum catalog as encyclopedia.

And there was Barnum. Barnum’s American Museum catalog is surprisingly mild-mannered, given the museum’s reputation. In some ways, it was a guide, but I imagine many of its buyers never made it to the museum, and it would work just as well for them. (Barnum got 12 1/2 cents for the catalog, and 25 cents for admission to the museum; he may have happy either way.) Like the Chinese Museum catalog, it describes a visit — “the power of the loadstone is shown to us in a very amusing manner,” or “in this room…the visitor sees.” It provides a non-visitor, or a potential visitor, the vicarious experience of a visit to the museum.

By the 1850s, a museum curator or exhibition impresario had a range of catalog styles to choose from. He might describe his collection, or his exhibition, or simply list the objects on display, or for sale. A catalog might serve as advertising or a sales tool. It might be part of a larger educational effort, using the collection to teach art, history, or natural history.

Notes

These essays are dedicated to the memory of David Jaffee, whose work at the Bard Graduate Center inspired their writing. They are based on a presentation to the Bard Graduate Center symposium on the New York City Crystal Palace, part of the opening ceremonies of the New York Crystal Palace 1853 exhibition.

For an overview of the early history of art museum catalogs, see Frits Keers, “Preliminaries for a Bibliography of Museum Collection Catalogues: Some Historical Observations on a Hitherto Neglected Aspect of Museum History,” Art Libraries Journal, January 1997.

Quicchelberg’s treatise is translated and explicated in The first treatise on museums: Samuel Quiccheberg’s Inscriptiones, 1565, ed. Mark A Meadow and Bruce Robertson (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2013).

On trade catalogs, see Lawrence B. Romaine, A Guide to American Trade Catalogs, 1744–1900. (New York: R.R. Bowker, 1960), https//catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001766919

On The East-India Marine Society of Salem, see James M. Lindgren, “`That Every Mariner May Possess the History of the World’: A Cabinet for the East India Marine Society,” New England Quarterly 68, no. 2 (June 1995): 179.

On the Chinese Museum, see Ronald J. Zboray and Mary Saracino Zboray, “Between ‘Crockery-Dom’ and Barnum: Boston’s Chinese Museum, 1845–47,” American Quarterly 56, no. 2 (2004): 271–307.

The need for a catalog for the natural history cabinet of New York is discussed in Documents of the Senate of the State of New York, 1846, 3, 6.

On art exhibitions in New York, see Carrie Rebora Barratt, “Mapping the Venues: New York City Art Exhibitions,” in Art and the Empire City: New York, 1825–1861, ed. Catherine Hoover Voorsanger and John K Howar (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000), 47.

The Whitman quote is from Loving, Jerome. “”Broadway, the Magnificent!”: A Newly Discovered Whitman Essay.” Walt Whitman Quarterly Review 12 (Spring 1995), 209–216. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.13008/2153-3695.1456

The Henry James quote is from A Small Boy and Others (1913).

The New York Times quote about the Naval Lyceum is from Vauc., “The United States Naval Lyceum,” New York Times, December 8, 1852. For more on the Naval Lyceum, see Steven Lubar, “‘To polish and adorn the mind’: The United States Naval Lyceum at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, 1833- 1889,” Museum History Journal, January 2014.