Museums can deal with Confederate Memorials

Moving Confederate memorials evicted from the public square to museums solves an immediate problem. It offers mayors and governors a way out of the corner that they find themselves in. But, for museums, it raises new questions. Should museums take them? What should they do with them? Would museums be seen as supporting the cause for which these memorials were erected? I believe that museums can work out creative ways to use these memorials.

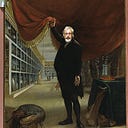

In art museums, Confederate memorials would find good company among the many paintings and sculptures that lost their political and cultural meaning when they moved from the court, the church, or the public square to the museum. Art historian Svetlana Alpers argues that “the museum effect” turns all objects into works of art. The statue of a Roman emperor that once declared his power becomes an example of late Roman statuary. A religious icon is no longer worshipped. A Confederate general on a horse displayed in an exhibit on equestrian sculpture has acquired a new meaning that overpowers the original intent of those who created it.

History museums offer a different kind of recontextualization. One of the first history museums, the late-eighteenth-century Museum of French Monuments, was created to hold art taken from churches and monasteries. It turned religious art became historical artifacts. Arranged in chronological order, transformed from religion to history, paintings and sculpture lost its cultural power.

The same thing will happen with Confederate statues moved from Southern cities and universities to history museums. While they have no place in an exhibit on the Civil War — a bronze Robert E. Lee on a 14-foot tall horse tells you nothing about strategy or tactics, the experience of battle, or why the war was fought — they will serve admirably to tell the history of the era so many were erected, the era of Jim Crow. Displayed next to a Klan robe and “whites only” signs, and perhaps postcards of lynchings, they will speak to the ways that a selective reading of history was weaponized to enforce white supremacy.

Memorials have a life beyond their dedication, and telling that longer story will also be important to museums. Did the memorial serve as a backdrop for annual speeches? Did parades march by? What did it mean to African Americans who had to walk by a reminder of the willingness of the fight to extend slavery? Museums need to tell the social history of these political memorials.

It’s essential to tell the story of the memorial’s removal. The activism that brought the monument down is as much a part of its history as the activism that erected it. The Durham Confederate soldier memorial, smashed by activists, tells that story beautifully. It could serve as a new memorial to twenty-first century Black activism, or, in a museum, tell a story of changing culture and politics, of organizing and resistance.

Memorials also offer an opportunity for an exhibit on how historical memory is used for political purposes. Monuments are one way that societies use history to shape the future. Haitian anthropologist Trouillot writes that monuments ‘‘impose a silence upon the events that they ignore, and they fill that silence with narratives of power about the event they celebrate.’’ A museum exhibition that calls attention to those silences forces memorials to tell those suppressed stories. It would help make sense of America’s memorial landscape. It would help visitors understand how history is shaped, and put to use.

When the Jefferson Davis statue at the University of Texas was moved to the University’s Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, Don Carleton, the director of the Center, made its new meaning clear. It was moved from “a commemorative context on campus to an educational one, where it will be accessible for viewing, study, and discussion.” The Briscoe Center would preserve it, and “place it within its broader history.” That’s the power of museums. It’s why they should step up to the opportunity to recontextualize some of the memorials being removed.

Museums are usually thought of as places of memory. But they are also places to forget. Moving art or artifact into a museum transports it out of the world of politics and daily life and into a shadow world: preserved, but powerless. Or, rather, with a new power, defined by its museum context. Dealing with Confederate memorials offers a curatorial challenge, but one worth taking. Historians, and museums will get the last word.

Steven Lubar is the author of Inside the Lost Museum: Curating, Past and Present (Harvard University Press, 2017). He teaches at Brown University.